|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Choosing a Welsh Pony or Cob, Showing Welsh, Welsh Breed Standard, pony growth, how much weight can a pony carry, breeding |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Articles on this page: How Much Weight can a pony/cob carry. Growth chart. Equine obesity and Insulin resistance. EMS & PPID |

|||||

|

The Equine back. Welsh Breed Standard with descriptions. More links. WPCSA Transfer Lists. |

|||||

| Equine Color Genetics by D. Phillip Sponenberg, DVM, PhD - Articles, Information, Opinions | |||||

| Articles on saddle fitting a pony and an arab (which is much like fitting a Welsh pony) | |||||

| http://www.saddlefitter.com/saddling_the_pony.htm http://www.saddlefitter.com/saddling_the_arab.htm | |||||

| AGE | |||||

|

Our Welsh pony mare Kressley's Talaria lived to the ripe, and healthy, old age of 39 years as pictured here. Talaria was an original type Section B. Can YOU see the Cob in her bloodlines?? Judges admired her "four square" conformation and bone. Talaria competed regularly with the kids in local Hunter Paces, trail rides and shows. Even once competing successfully in the Essex County Pony Race, coming in second to a small thoroughbred! Talaria LOVED to be in front! This is a true to type Section B Welsh pony.

|

|||||

| HOW MUCH WEIGHT

CAN A PONY OR COB CARRY? Generally speaking a Section A Welsh pony is mentally and physically mature enough to start under saddle lightly at three years. Section B Welsh ponies don't mature mentally until at least four years and physically until 6 years, and this goes for the Section C Welsh pony of cob type and the Section D Welsh cob also. As everyone knows horses truly mature later than a pure pony breed; and those pony breeds that have had horse blood introduced for size also mature later both mentally and physically. Please see the article below which explains the physiology of growth. It is important to take into consideration the changes the Welsh go through between their first and fourth year. A pony that was born with obvious good bone and depth of body is most likely to carry those attributes when mature. A pony born slight of frame and bone, though elegant looking, will also carry those attributes in their maturity and more importantly will throw those attributes when bred. You can cross a light animal to try to produce elegance with "bone and body" and meet with some success, but the success will be hit and miss for quite a few generations. Better to start with a pony "to the breed standard" than try to create one. Why the difference? I believe it is because the Section A Welsh pony for the most part is a pure pony breed, though most did have some Arabian introduced in Great Britain. For the most part that outside blood was introduced from the 1600's thru the early 1700's and was not introduced specifically for size, but rather for refinement of type. Though we can see the change in type from the Arabian influence, that influence is well beyond the 20th generation. To truly see the change in the Section A type it is well worth while searching the Hill Pony preservation groups in Wales. See the information and link below. The Section B Welsh ponies had various outside breeds introduced to their bloodlines right up to the early 1900's. The refined, elegant type became the "fad" of the years, as in the British Riding Pony, and subsequently became the "type" of Welsh "riding pony" bred for. If you consider that many breeders then concentrated their lines on ponies carrying those outside lines, some Section B's have Thorobred and Arabian blood right up to the 10th generation. The Section D cobs generally had Hackney horse blood, Standardbred, Akhal Teke, Thorobred, Arabian, Barb and other breeds introduced from the early 1600's on. I have had many people ask how much weight can a pony or cob carry. What I tell them is that it depends on the age and the structure of the animal. NO pony or cob should be asked to carry a heavy load before it reaches six years of age. Over burdening an animal does nothing but stress the joints which will limit their use-ability in years. We had a Section B mare of good bone and body, more the original type of Section B, who was not started under saddle until her seventh year and who finally passed on at 39 years old completely sound. The structure of the animal must be taken into consideration, a light boned, light bodied animal will be less able to carry weight over a long period than a strong boned and bodied animal. That said, generally a pony or cob can carry up to 20% of their weight; if you are speaking of riding, that weight would include the tack used. Section A ponies usually are 500-550 lbs at maturity so should be able to carry 100-110 lbs comfortably. Section B ponies can go from 600-850 lbs and should be able to carry 120-170 lbs; Section C ponies are generally the same. Section D Cobs have such a difference in size range that one would have to go by the 20% of their weight figure. We have a Section D who is 950 lbs and should be able to carry up to 190 lbs, and several Section Ds that are 1200 lbs (and over) and should be able to carry 240 lbs or more. Again, age and structure should be considered. All animals can pull more than they can carry. |

|||||

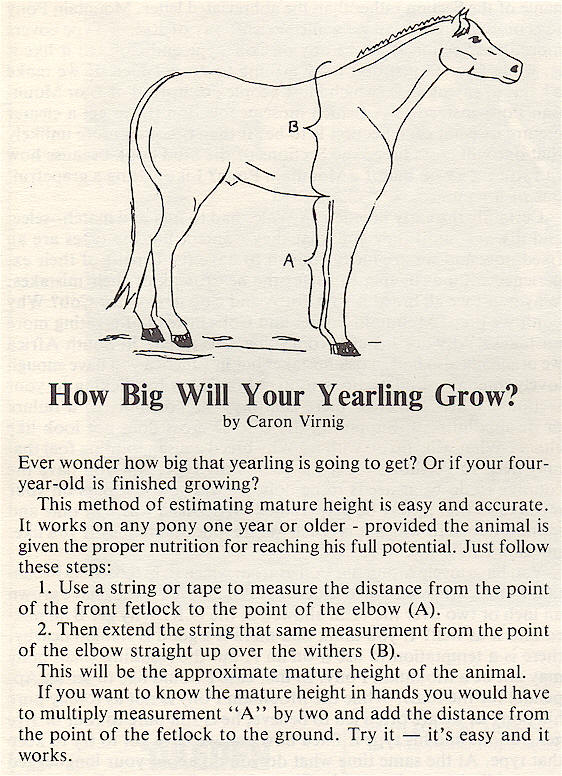

| How big will your yearling become | |||||

|

|||||

| WARNING - QUEST WORMER | |||||

|

Quest can be a very dangerous product to use. As instructed on the box you must make sure you do not use it on youngstock. Anything under 2 years of age receives a different product. Quest is a very potent product, and it's crucial that you follow the directions in regards to how much to dispense to each pony…..as you should with any medication. It is definitely not a product I would use on a really wormy horse or pony, rescue, etc. Do not consider using Quest on an abused or rescued animal that is bone thin. Wait until the pony or horse starts gaining weight, then deworm it at that point with another product and wait until the animal is back to being healthy again before using a Quest product, if you feel it necessary. There have been instances of perfectly healthy animals dropping dead within 48 hours of administering a regular dose of Quest. Some symptoms an animal may show as a reaction to Quest are colic and then organ failure. Attempts to save an animal may be in vain, as with at least one animal experience the vet ultimately had to come back and put it down. In this instance the response from the pharmaceutical company was less than encouraging. They simply didn't care and without having an autopsy done they really don't care This was not the first, and won't be the last to have had a negative and deadly encounter with Quest. |

|||||

| EQUINE OBESITY | |||||

| Many people feel that a fat pony or cob is preferred by judges, what they are not considering is that Equine obesity increases a horse's risk for equine metabolic syndrome, laminitis, and insulin resistance. Owners can bring horses to a healthy body condition by replacing grain rations with a fiber-rich, low-carbohydrate diet and increasing exercise. Exercise will replace the fat with muscle, muscle increases fitness, the animals ability to move well, and be judged easily on fitness and movement. Read More at TheHorse.com | |||||

|

Understanding the Differences between EMS and PPID By University of Kentucky College of Agriculture Jun 28, 2013 Topics: Cushing's Disease Metabolic Syndrome Older Horse Care Concerns |

|||||

|

Equine Medical & Surgical Associates http://www.equinemedsurg.com/ir1.html Insulin Resistance in Equines I. What is Insulin? A. Insulin is a hormone produced by an organ in the abdomen called the Pancreas. Using a Quarter Horse for reference, the Pancreas is about two feet behind the girth of the saddle on the right side and weighs approximately ¾ of a pound. About 98% of the Pancreas produces enzymes to break down food in the gut and only 2% make hormones such as Insulin. Hormones are chemicals produced by one type of tissue that are transported to target tissues that have special receptors for the hormone; once the hormone and the receptor connect, the hormone will facilitate reactions inside the target cell. B. Insulin has many jobs and many targets. Insulin has direct action on all cells in the body (except the brain), and helps in carbohydrate, protein, and fat breakdown products entering the cells. Insulin’s main job involves carbohydrate metabolism. Insulin release from the Pancreas is triggered by rising levels of carbohydrate in the bloodstream. The carbohydrate that causes this Insulin outflow is called Glucose. As Glucose levels rise, Insulin levels will rise and when Glucose levels go down, less Insulin is released from the Pancreas and hence Insulin levels go down. There are several ways for Glucose levels to go up, but by far, the biggest rise comes after your horse eats. In hay and grass, carbohydrates are the main type of nutrient, with protein second, and fat the third type. In magazines, carbohydrates are often referred to as “sugars” or “starches”. Starches are actually long chains of thousands of Glucose molecules linked together. As your horse chews, he is starting the process of breaking down starch to release the simple sugar unit of Glucose. Saliva enzymes, stomach acid, and small intestine enzymes further breakdown starch into individual Glucose molecules. Once these Glucose units get into the small intestine, they are absorbed out of the digestive tract and into the bloodstream. After a meal, large quantities of Glucose pour into the bloodstream. Blood Glucose levels are now rising. In literature, blood Glucose is often referred to as the “blood sugar”. This high level of Glucose circulates to the Pancreas and will trigger the Pancreas to release Insulin into the bloodstream. Now we understand Insulin’s source and what causes it to go up and down, which leads us to what it does. C. Equine Insulin Resistance in horses is the correct term to use when they get pathologically high levels of Insulin. There are many other terms that have been used in the past that are inaccurate or confusing such as:

D. Insulin is crucial in promoting Glucose in the bloodstream to move into cells. Glucose is the major fuel used by cells for energy. Again, Insulin has many target tissues but the most important are muscle, fatty tissue, and the liver. How Insulin gets Glucose into cells is much like a lock and key. On the muscle cell, for example, are thousands of receptors waiting for Insulin to arrive. The receptor is the lock and Insulin is the key. When the key fits the lock, it allows Glucose to enter the cell. As Glucose goes from the bloodstream into the cell, the blood Glucose level will drop and hence the output of Insulin from the Pancreas will drop. Glucose transport into muscle and fatty tissue goes up 5-20 times in the presence of Insulin. This fact highlights how important Insulin’s action is in obtaining energy for the cell. E. Regarding fatty tissue which is another target tissue for Insulin: 1. Insulin promotes Glucose into fat cells which help in fat

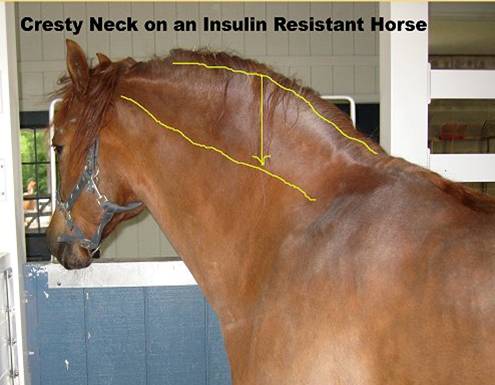

synthesis. This is a “triple-barrel shotgun effect” — all of which promote fat. This action by Insulin is normal in your horse but you can already hear warning bells if things go wrong. Too much Insulin means too much fat and that puts weight on your horse. II. Insulin Resistance A. Defined Inability to respond to and use Insulin the body produces because Insulin is not functioning properly; higher Insulin levels are needed to achieve the same effect. There is an abnormally high amount of Insulin circulating for long periods of time that leads to diseases such as Laminitis. Normally, we know the usual level of Insulin throughout the day and know that after a grain meal, the Insulin level will go up 3-4 times the regular level due to Insulin responding to Glucose pouring into the bloodstream. The short-term high level of Insulin is normal Hyperinsulinemia and lasts only a few hours. In Insulin Resistance, the base level of Insulin is about 3 times higher, so there is a constant elevation during the day. When an Insulin Resistance horse has a grain meal, there is a pathological Hyperinsulinemia that sees the level of Insulin go up 30, 40, 50, and over 100 times usual levels, and can remain elevated much longer than normal. This stark fact highlights the reason behind the need to control insulin! A pony with a cresty neck is 19 times more likely to have Insulin problems. Horses with both Cushing's & Insulin Resistance need help fast. According to the American Diabetes Association, people with insulin resistance and diabetes have a 7-12 year decreased life span. In a horse, that translates to losing 2.5 to 4.5 years of life. B. What is causing the condition? Basically, the key and lock system is broken. There are several ways this occurs and they can occur separately, or combine to do multiple damage. Ways to cause Pathological Hyperinsulinemia:

The final result that the target cells are resisting to work normally with Insulin (hence the name Insulin Resistance) which causes the Pancreas to try to overcome the resistance by pouring out more and more Insulin. In Insulin resistance, this higher and higher level of pathological Hyperinsulinemia is able to still push Glucose into the cells and maintain normal blood Glucose (blood sugar) levels. Rarely in horses, the higher Insulin levels can not overcome all the problems and the blood Glucose levels can not be maintained and start to stay elevated— this is called Early Stage Type II Diabetes. In these rare cases, the horse has sky-high Insulin and sky-high blood Glucose. To get to Type II Diabetes, you first have to be very Insulin resistant to the point you can not maintain Glucose levels. Often, Insulin Resistance is mistakenly called Diabetes or Type II Diabetes in the horse. The reason for this is because in people, Type II Diabetes is the most expensive disease process in humans, the fastest-growing disease process in humans, and now the #1 cause of blindness in humans. Your horse probably has Insulin Resistance because they can still maintain normal blood Glucose levels. C. What conditions are breaking the lock and key system in my horse? 1. Toxins from fat cells. 1. If your horse is overweight at an early age, they can have 3 times the number of fat cells as a regular horse. Some fat cells release toxins that interfere with Insulin’s action at the target cell. 2.

If your horse is overweight: 3. Most Insulin Resistance horses are over weight. A recent University of Virginia/Maryland report estimates 50% of the horse population is over weight and 20% are obese (Obese is over 20% beyond ideal weight). In addition, if a horse is obese, about 1/3rd of them will have Insulin Resistance. 2. Insulin Insulin at very high levels starts to interfere with other Insulin’s ability to get to receptors. The keys are

breaking each other. This is “negative cooperatively”. 3. Cushings Disease Can lead to Insulin Resistance in several different ways. The horse can have Cushings and Insulin Resistance at the same time. Why? 1. High ACTH levels in Cushings can directly interfere with Insulin’s action. ACTH is damaging the keys. 2. High ACTH levels lead to Cortisol abnormalities. Cortisol is responsible for increasing blood Glucose levels by causing stored sugars in muscle/liver to be released. The higher levels of Glucose trigger more and more Insulin. 3.

Cortisol, like ACTH, can directly interfere with Insulin’s action. More keys are damaged. 4. Stress Mental/Physical— surgery, infections, shipping... 1. Increased Epinephrine causes increased ACTH, increased Cortisol, leading to more Insulin Resistance. 2. Increased Cortisol will interfere with sleep, so more stress. 3. Increased Cortisol will depress immune system leading to more infections that lead to higher Insulin levels. 4.

Increased Cortisol breaks down muscle which results in muscle weakness— often see in Cushings horses 5. Increased Cortisol decreases muscle synthesis. 5. New study via Dr. Reilly – “Insulin Resistance – New Triggers”. More research results pending. |

|||||

|

WPCSA Transfers List

|

|||||

|

Dr. Deb Bennett - Growth and Training "I want to address the issue of maturity and deal with that concept thoroughly. |

|||||

| TheHorse.com | Welsh examples from the Breed Standard | ||||

|

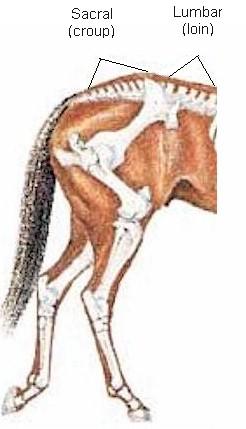

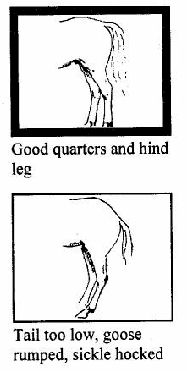

The Equine Back by Les Sellnow A key part of back conformation is the loin—the area between the last rib and the croup. The loin should be well-muscled, strong, and relatively short so that it can convey power from the rear legs forward. The croup is the area that extends from the loins to the tailhead. It should be long and gently sloping, with the amount of slope varying from breed to breed and horse to horse. A long croup enables a horse to have a long stride as well as providing a setting for proper dimension and solid muscling in the hindquarters.

|

|

||||

| Now apply the above information to the Welsh Breed Standard picture below. | |||||

| Welsh Pony and Cob Breed Standard with descriptions | |||||

|

|||||

| Breeders should

remember that a short, strong back is required in Stallions; in mares a strong but longer back is acceptable because the need for room to carry a foal is required. However, this does not excuse a long, weak back in mares. |

|||||

| WPCS Breed Standard Pamphlet given to new members in the 1970's | |||||

| The Welsh Pony Book circa 1914 | |||||

| Criban Victor | |||||

| Judging | |||||

|

THE WELSH PONY AND COB SOCIETY OF AMERICA Articles of Incorporation, ByLaws, Rules of Not for Profit, etc. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

At the meeting of Members Services on Tuesday 13th November, the subject of white markings was discussed. A solution was framed to go before Council on Monday December 10th where it was passed unanimously. As the subject is of significant interest to members we feel it appropriate to post the general outline of the solution accepted by the Council in advance of the minutes. The Council of the WP&CS has agreed to amend the regulations for entry to the Stud Book to read: Colour: Any colour, except piebald and skewbald including tobiano and overo patterns. Excessive white should be discouraged. In the showring Judges will be empowered to judge according to personal preference. This will be highlighted in the Judging and Showing Handbook that will be published in January. Penalties for not supplying the correct colour and markings would be immediate withdrawal of the members’ right to complete colour and markings on registrations. Further penalties could extend to disciplinary proceedings or trading standards. Following this clarification of regulations, animals registered within Section X of the Stud Book can be reviewed by the Members Services Committee. Individuals wishing to appeal should do so in writing to the Society at 6 Chalybeate Street, Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, SY23 1HP. |

|||||

|

At the insistence of their membership The Welsh Pony and Cob Society of Great Britain hired a Consultant to review the

organization and make recommendations to improve their methods of operation, and the perception of the organization by members and the public.

It is obvious, by what is pinning at the Royal Show, that it has not done an ounce of good. See the information here. |

|||||

| However, it is clear that there are some responsible breeders that realize the worth and importance of preserving the original hill ponies and their genetics. | |||||

| Disclosure: We are a review site that receives compensation from the companies whose products we review. We test each product thoroughly and give high marks to only the very best. We are independently owned and the opinions expressed here are our own. | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Copyright © Cross Creek Welsh Ponies 1969 |

|||||