|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

EQUUS SURVIVAL TRUST ... KEEPING THEM SAFE and PURE The Equus Survival Trust is a |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home |

Email Denise at crosscreekwelsh@gmail.com |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Equine Color Genetics by D. Phillip Sponenberg, DVM, PhD - Definition of the Paint/Pinto Overo color and it's Derivatives Sabino and Splash White |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

x An Introduction to Heritage Breeds ... Dr. Phillip Sponenberg, Jeanette Beranger, Allison Martin |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Articles from Welsh Magazines and Books on Breeding Welsh Ponies and Cobs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Defining Bloodlines and Strains Within Breeds |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By Phil Sponenberg, Jeannette Beranger, and Marjorie Bender |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ALBC members frequently ask "what is a "bloodline" or "what is a strain"? These terms are tricky to define and often misunderstood. Many breeders struggle to understand exactly what these terms mean. Breaking down the basics can shed light on the concepts involved, and help define these basically synonymous and interchangeable terms. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The simplest definition is that a bloodline or strain is a group of animals within a breed that are themselves somewhat distinctive compared to other individuals of the same breed. This distinctiveness is usually both by physical type as well as by bloodline or pedigree. In this sense, a bloodline or strain is basically a "sub-branch" of the main "branch" that is the breed. The breed is a branch off of the main species trunk. The branching pattern goes: Species - Breed group - Breed - Strain/Bloodline. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It is easiest to appreciate and define a bloodline/strain by looking retrospectively. A strain is different from the main breed by some amount of isolated breeding, and usually a distinct foundation event. When looking towards the future, the question of "what does it take to make a strain?" gets tougher. Basically, the same components of a reasonably unique foundation, genetic isolation, and owner selection come into play. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The problem of defining a strain is very similar to the problem of defining a breed. Deciding exactly where to cut either one off is often perplexing. "We know it when we see it" rarely cuts the mustard, but is unfortunately close to the truth! But, saying that strains have at least four generations of closed breeding with no outside introductions is a start and will stand up to scrutiny in most cases. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It must be added though, that outside breeding within the breed is occasionally allowed, and even necessary, or strains become genetic deadends. The key is what happens after the outcross. The results of the outcross should be mated back into the strain, in what is essentially and "upgrading" process. This needs to result in at least 75% (or better 87.5%) the influence of the original strain in order to be considered part of that original strain. This requires two or three crosses back to the original strain. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| An important issue in any discussion of strains and bloodlines is the question "why are bloodlines and strains important"? The bloodlines within a breed can be very important reservoirs of genetic variation. Managing these within the overall breed is important for long-term breed survival. When some strains gain significant popularity and overwhelm the presence of other strains in the breed by marginalizing them or driving them to extinction, the result is decreased genetic health for the breed as a whole. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Understanding the role of strains and bloodlines in maintaining genetic health for a breed is essential for all serious breeders. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| For more information on this topic, see "Chapter 4: Maintaining Breeds" in Managing Breeds for a Secure Future: Strategies for Breeders and Breed Associations by D. Phillip Sponenberg and D.E. Bixby. American Livestock Breeds Conservancy, 2007. The book can be purchased through the ALBC website or by calling 919-542-5704. Price: $22.95 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The observable

phenomenon of hybrid vigor stands in contrast to the notion of breed purity. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

LINE BREEDING Consider this: The Thoroughbred as a breed originated from just three stallions. The Godolphin Arabian, the Byerly Turk and the * Darley Arabian. In fact, recent research found that, in 95% of modern Thoroughbred racehorses, the Y-chromosome can be traced back to the Darley Arabian! Possibly the most important tool a horse breeder has at their disposal are the pedigrees of their breeding stock. After everything else has been considered (from conformation to coat colour and absolutely everything else possible in between.) - the intelligent and competent use of a pedigree is what separates a skilled horse breeder (i.e. a breeder with an ‘eye’ for a horse) and someone who simply breeds animals they like hoping the result will be successful. The most respected and successful breeders, amongst others, throughout time have employed line breeding of their finest animals as their key tool to create equine masterpieces The purpose and point of line breeding is simply to produce horses who can pass on their [superior] traits i.e. homozygosity. One line breeds in order to set the desired characteristics by increasing homozygosity, which allows a horse to pass on their traits generation after generation. Line breeding sets the ‘type’ (i.e. phenotype) and genetic material (i.e. genotype) thereby allowing the horses to reproduce themselves accurately and reliably. This entrenches (by doubling up or tripling up - depending upon the extent of the line breeding) the desirable traits when one is developing a breed or a type for a specific purpose. This should only be practiced with superior quality animals, with no conformational defects or heritable abnormalities and that, in the case of a sire, he is prepotent and his offspring bear all his good attributes. It goes without saying that one uses both the conformation of the said animals as well as the pedigree when making breeding decisions. It is not sufficient to go simply by pedigree alone, or by phenotype alone. The two are inseparable. It is safe to say that to breed a great horse one needs great parents. However, of absolute equal importance are the grandparents and their parents, and so it goes on. In fact, every single horse in the pedigree is important—the closer up it is, and the more it is line bred to, the greater its importance. Apart from requiring a very high standard of conformation, they must have excellent temperaments. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Excerpt - Welsh Pony Book circa 1913 (click on title) ....... there were too many doors left carelessly open. The larger pony of the lower lands was becoming mixed with Cardinganshire cob; and some owners

were guilty of letting half-bred Shire

by Olive Tilford Dargan, Printed privately for Charles A. Stone : 1913

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Excerpts from A Conservation Breeding Handbook published for The American Livestock Breeds Conservancy by D. Phillip Sponenberg and Carolyn J. Christman |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chapter 8. The Context of Conservation Breeding |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The ALBC encourages the protection of genetic diversity through the effective conservation of livestock and

poultry breeds. The diversity represented by many genetically distinct breeds is necessary for the long term health and utility of each domestic species. Breed conservation has five elements, each one essential for success: 1. A knowledge of breed history and characteristics, including production parameters. Numerical Status (be aware that this would have to be determined in and by individual countries) The numerical status of a breed can be considered first, how many individuals of the breed exist? One can answer this question by estimating the number of adults or the number of adult males and females. Such information is usually difficult to come by. Since breed registries generally do not record deaths of individuals, the registry may have a cumulative total of all individuals registered but not know the number still alive..... Numerical and genetic status: effective population size When the exact number of male and female parents used to produce a given generation of a breed is known, then a numerical calculation called "effective population size" can be obtained. A simplified equation to describe effective population size is: Ne = [4 x Nm x Nf] Ne = the effective population size; Nm = number of male animals; and Nf = number of female animals The effective population size equation demonstrates that the size of a population does not necessarily reflect its genetic status, and an increase in numbers alone will not necessary protect genetic diversity. Instead, the number of parents used to produce each generation is critical. The number of male parents is most relevant since generally fewer males than females are used in breeding. If only a few males are used to produce a generation of offspring, genetic breadth will be substantially reduced, regardless of the number of females used...... Heritage, Habitat, and other factors Despite the utility of mathematical calculations, the genetic status of a living breed is very difficult to describe and will always remain somewhat subjective. Among the elements of a breed's genetic heritage is the existence (or lack thereof) of distinct, isolated bloodlines, which have high genetic value for a breed. These lines represent genetic materials which has been long divergent from the breed as a whole and can be used to provide linecrossing and some hybrid vigor. Included in any measure of breed status is the status of its habitat. The number and location of herds is an especially important indicator of status, ......... but is an issue for all species. A second element of habitat is the selection of breeding stock practiced by human breeders, and the ways that selection is evolving to fit market conditions. What are breeders' goals for the breed? It is important to know whether current selection pressures fit the historical background of a breed. Intense selection that seeks to mold the breed into a different direction can cause genetic erosion. Breeds which have a current market niche consistent with their historical uses are in a far better position than those which lack this opportunity. The network of people who promote a breed, as well as the resources available to the breed are an important part of its habitat. the strength or weakness of a breed association and the vision of a breeder community serve to make a breed either more or less secure. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Conservation Breeding Handbook is available at http://albc-usa.org/ for $15.95, along |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

with many other useful, unbiased and intelligent resources. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

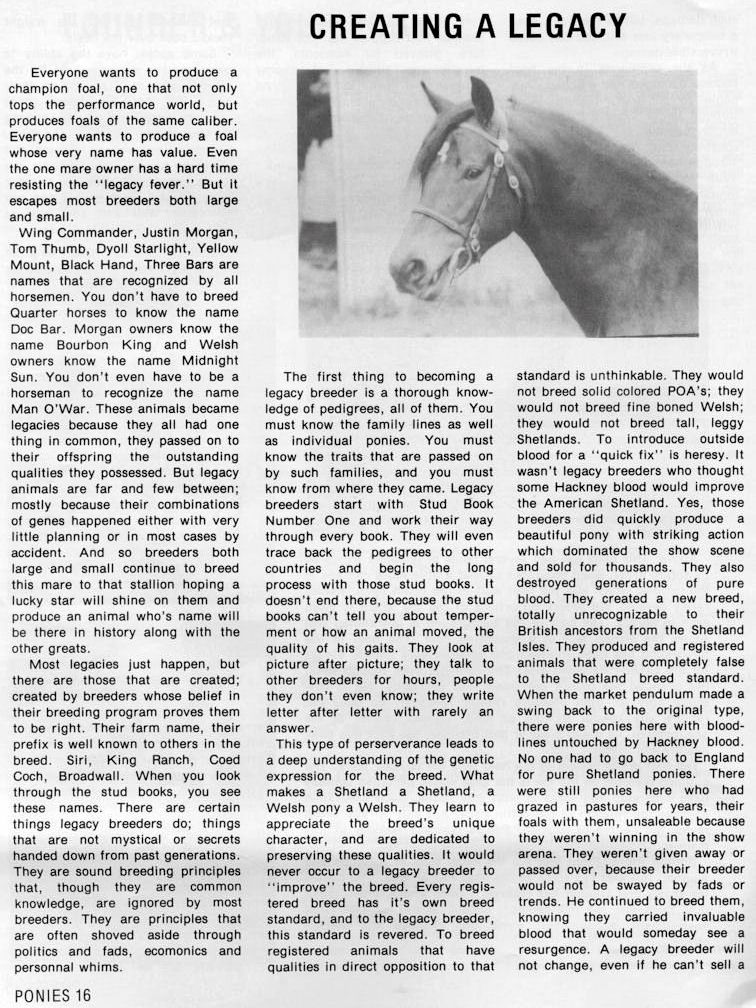

| We believe in the "partnership" and the "trade" concept. By doing so we can keep our

breeding goals fresh by partnering with or trading breedings with others who have the same goal, Welsh ponies bred to the Breed Standard with pony

character, type, conformation, movement and disposition. There is no scientific proof that linebreeding and inbreeding if done correctly is wrong.

To the contrary, linebreeding and inbreeding are the ONLY way to produce and set type in an animal. Linebreeding and inbreeding were utilized by

the most famous, influential breeders from the beginning of time. Liseter, Severn, GlanNant, Bristol, Lithgow, Grazing Fields and Farnley ponies in the US

(to name a few) were developed through just such planning following the examples of the UK Criban, Clan, Dyoll, Eiddwen, Cymro, Ystrad, Pentre, and

Forest were some of the oldest recorded studs in the UK on which breeders based their lines, including the Coed Coch stud (although in many cases the Coed

Coch indiscriminate use of Arabians crossed on their Welsh did not do the breed justice). In the "old days", when Welsh ponies and cobs were not a

financial commodity, the Welsh that were imported were the best available from the UK. And, as a matter of fact, many of those were of foundation lines

since lost to the UK. However, common sense tells us that breeders now do not sell their best stock unless they choose to change their breeding operation

from one section of the registry to another. In the UK, where much of what is considered the best stock, especially in the Section B's, are nothing more

than crossbred ponies, better compared to the British Riding Pony. Criban Victor was one of the only Section B stallions (a multi British Royal Champion)

carrying cob blood to increase size, not a concentration of thorobred and Arabian blood. This told to us personally by several UK breeders who have

lamented over their loss of Criban Victor who had so much to offer the development of Section B ponies. Culling was used by early breeders not only to recoup their costs of producing an animal, but to remove an animal from the gene pool which they considered not of breeding quality to their standard. Culling can be accomplished by many methods, sale to an unknowledgeable person is one, sale without registration is another, and finally sale at a "meat" auction. "Meat" auctions were and are a viable way to recoup production costs. Nowadays reputable breeders sell the same pony without papers or with papers, without describing the undesirable qualities a pony possesses whether visible or invisible to the naked eye. Yet we still find people trying to get papers for unregistered Welsh ponies all the time. If a breeder chose not to register the pony or sold the pony without papers there WAS a reason, and as the breeder his/her decision to cull should be respected, these ponies should remain unregistered and not thrown back into the Welsh gene pool. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

How to calculate the percentage of genetic influence in your pony’s pedigree. Each parent provides 50% of the genetic make-up to a foal. The following chart gives you the percentage of genetic material coming from each horse in that generation. An old "saying" indicates that a horse must carry at least 18% of a certain individual in the pedigree to see any potential real physical or mental influence from that ancestor. When a common ancestor appears, you add together each percentage level to determine the total overall influence. Multiple common ancestors: add together each common ancestor to get the total genetic influence coming from that horse.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Ins and Outs of Pedigree Analysis, Genetic Diversity, and Genetic Disease Control As breeders, you engage in genetic "experiments" each time you plan a mating. The type of mating selected should coincide with your goals. Outbreeding brings together two animals less related than the average for the breed. This promotes more heterozygosity, and usually more variation in a litter. A reason to outbreed would be to bring in new genes or traits that your breeding stock does not possess. Outbreeding can also mask the expression of recessive genes, and allow their propagation in the carrier state. Linebreeding attempts to concentrate the genes of a specific ancestor or ancestors through their appearance multiple times in a pedigree. The ancestor should appear behind more than one offspring in the sire and dam's pedigree. Otherwise you are only linebreeding on the single offspring. A linebreeding may produce an offspring with magnificent qualities. However, if those qualities are not present in any of the ancestors that have been linebred on, the individual may have a wonderful show career, but it may not breed true. Careful selection of mates is important, but careful selection of offspring from the resultant litter is also important to fulfill your genetic goals. Without this, you are reducing your chances of concentrating the genes of the linebred ancestor. Inbreeding significantly increases homozygosity, and therefore uniformity in litters. Inbreeding can cause the expression of both beneficial and detrimental recessive genes through pairing up. Inbreeding cannot change, or create undesirable genes. It only exposes them through homozygosity. Inbreeding can also exacerbate a tendency toward disorders controlled by multiple genes, such as hip dysplasia and congenital heart anomalies. Unless you have prior knowledge of what milder linebreeding on the common ancestors has produced, inbreeding may expose the offspring (and buyers) to risk of genetic defects. Research has shown that inbreeding depression, or diminished health and viability through inbreeding is directly related to the amount of detrimental recessive genes present. Some lines can thrive with inbreeding, and some cannot. The inbreeding coefficient is an estimate of the percentage of all the variable gene pairs that are homozygous due to inheritance from common ancestors. It is also the average chance that any single gene pair is homozygous due to inheritance from a common ancestor. In order to determine whether a particular mating is an outbreeding or inbreeding relative to your breed, you must determine the breed's average inbreeding coefficient. The average inbreeding coefficient of a breed will vary depending on the breed's popularity or the age of its breeding population. For the calculated inbreeding coefficient of a pedigree to be accurate, it must be based on several generations. Inbreeding in the fifth and later generations (background inbreeding) often has a profound effect on the genetic makeup of the offspring represented by the pedigree. In pedigree studies, the difference in inbreeding coefficients based on four versus eight-generation pedigrees varied immensely. A four-generation pedigree containing 28 unique ancestors for 30 positions in the pedigree could generate a low inbreeding coefficient, while eight generations of the same pedigree, which contained 212 unique ancestors out of 510 possible positions, had a considerably higher inbreeding coefficient. What seemed like an outbred mix of genes in a couple of generations appeared as a linebred concentration of genes from influential ancestors in extended generations. Many breeders plan matings solely on the appearance of an animal and not on its pedigree or the relatedness of the prospective parents. This is called assortative mating. Breeders use positive assortative matings (like-to-like) to solidify traits, and negative assortative matings (like-to-unlike) when they wish to correct traits. Some individuals may share desirable characteristics, but they inherit them differently. This is especially true of polygenic traits, such as ear set, bite or length of forearm. Breeding two phenotypically similar but genotypically unrelated individuals together would not necessarily reproduce these traits. Conversely, each individual with the same pedigree will not necessarily look or breed alike. Therefore, matings should be based on a combination of appearance and ancestry. Rare breeds with small gene pools have concerns about genetic diversity. Some breed clubs advocate codes of ethics that discourage linebreeding or inbreeding, as an attempt to increase breed diversity. The types of matings utilized do not cause the loss of genes from a breed gene pool. It occurs through selection; the use and non-use of offspring. Regardless of the breed, if everyone is breeding to a single stud, (the popular sire syndrome) the gene pool will drift in that individual's direction and there will be a loss of genetic diversity. The frequency of his genes will increase, possibly fixing breed related genetic disease through the founder's effect. If some breeders linebreed to certain individuals that they favor, and others linebreed to other individuals that they favor, then breed-wide genetic diversity is maintained. Animals who are poor examples of the breed or who do not consistently produce the characteristics and traits expected and desired should not be bred to maintain diversity, but should be discarded and the breeding program should be re-evaluated. Related individuals with desirable breed qualities will maintain diversity, and improve the breed. If you linebreed and are not happy with what you have produced, breeding to a less related line immediately creates an outbred line and brings in new traits. Repeated outbreeding to attempt to dilute detrimental recessive genes is not a desirable method of control. Recessive genes cannot be diluted; they are either present or not. If an individual is a known carrier or a high carrier risk through pedigree analysis, it should be retired from breeding, and replaced with one or two quality offspring. Those offspring can be bred, and replaced with quality offspring of their own, with the hope of losing the defective gene. Trying to develop your breeding program scientifically can be an arduous, but rewarding, endeavor. By taking the time to understand the types of breeding schemes available, you can concentrate on your goals towards producing a healthy and worthy representative of your breed. Jerold S. Bell, DVMTufts University School of Veterinary Medicine North Grafton, MA Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Michael Bowling, the well-known American geneticist and CMK [Crabbet/Maynesboro/Kellogg] breeder, who had just presented a paper on SCID at the WAHO Conference in Turkey, then spoke to us on the principles of Preservation Breeding. He encapsulated some important thoughts in his own precis: "Maximum genetic diversity is maintained, not by working with homogeneous populations, but by allowing subgroups to develop. Practical breeding groups may be a single large breeding program, a circle of co-operator breeders, or a defined subset of a breed. Any of those may develop finer substructure, as trends develop over time. Wilfrid Blunt himself wrote that it would be desirable to develop a sub-group at Crabbet with no Mesaoud, which would have allowed a built-in outcross for the future - but an outcross to the same kind of horse, Our task today would be far simpler if that kind of long-term plan had been implemented; our counterparts in the future will have breeding options defined by what we do in our turn." Also: "Traditionally the Arabian horse has been a highly selected using and companion animal: our goal in Arabian preservation breeding must be to select within our stock to combine the best traits of the traditional Arabian. By "improve" we mean, to produce better examples of the same kind of horse. We must not be led astray by the false notion of breed improvement which means to make the Arabian into a different kind of horse." http://www.crabbetarabian.com/article.html | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Socioeconomic Causes of Loss of Animal Genetic Diversity The number of breeds of domesticated animals, especially livestock, have declined rapidly. The proximate causes and processes involved in loss of breeds are outlined. Also the path-dependent effect and Swanson's dominance-effect are discussed in relation to lock-in of breed selection. While these effects help to explain genetic erosion, they need to be supplemented to provide further explanation of biodiversity loss. In the respect, it is shown that the extension of markets and economic globalization have contributed significantly to the loss of breeds. In addition, the decoupling of animal husbandry from surrounding natural environmental conditions, particularly industrialised intensive animal husbandry, is further eroding the stock of genetic resources. Recent trends in animal husbandry raise serious sustainability issues, apart from animal welfare concerns. Clement Allan Tisdell ,School of Economics The University of Queensland Brisbane QLD 4072 Australia

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

articles and pictures OF WELSH PONIES AND COBS - BREEDING, SHOWING, BLOODLINES AND MORE |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Disclosure: We are a review site that receives compensation from the companies whose products we review. We test each product thoroughly and give high marks to only the very best. We are independently owned and the opinions expressed here are our own. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright © Cross Creek Welsh Ponies 1969 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||